"On earth peace, good will toward men." Luke 2:14b (KJV)

The alien conditions of a stagnated war where most regular enlisted men were already buried under the shell-torn land combined and torrential rain made the newly-disturbed earthen trenches swamps of precipitous mud established an unspoken agreement from both sides to adopt a "live and let live" policy that allowed certain activities and locations to go unmolested by the constant aggression of the war.

Charles Sorley, a British officer and poet wrote, "During the night a little excitement is provided by patrolling the enemy's wire. Our chief enemy is nettles and mosquitoes. All patrols - English and German - are much averse to the death and glory principle; so, on running up against one another . . . both pretend that they are Levites and the other is a good Samaritan - and pass by on the other side, no word spoken. For either side to bomb the other would be a useless violation of the unwritten laws that govern the relations of combatants permanently within a hundred yards of each other, who have found out that to provide discomfort for the other is but a roundabout way of providing it for themselves."

This close proximity led to units bantering back and forth with jests, insults, and songs. The same miserable conditions between enemy regiments over several months laid the foundation for one of the most remarkable events of the war. The Germans held Christmas Eve as the most important day of Christmas festivities and erected Christmas trees embellished with candles along the trench lines against official orders. The lights initially confused British and French forces, but the singing of "Stille Nacht Heilige Nacht (Silent Night, Holy Night)" cemented the tidings of the season. On Christmas day, wines, cakes, and trinkets were exchanged by both sides and, possibly, impromptu games of football took place over parts of No Man's Land not pocketed with shell craters. The Christmas surplus issued by governments to their enlisted men provided the perfect establishment for a barter-like Christmas celebration.

Not all regions of the trenches saw the joviality of comradery, but for the segments still entangled by the bitterness and death of war, Christmas day passed relatively quietly as each side was left to celebrate more or less on its own. Overall, the truce seems to have been quite extensive although unofficial and against the orders of high command. The Christmas truce of 1914 was inconsistent with a widely varying involvements and fraternization, but for most combatants, Christmas was a peaceful day, for many the week to New Years was quiet, and for a lucky few the unofficial holiday celebrations continued well into January.

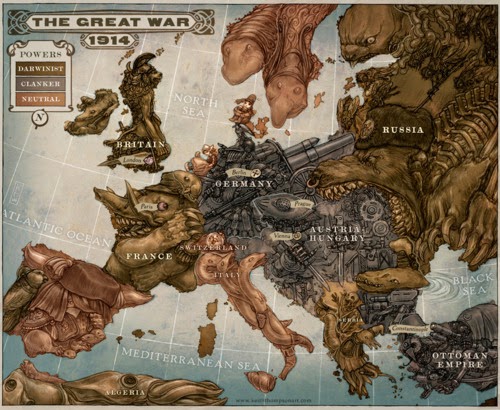

Hundreds of stories, recorded in letters to home, tell of interactions between British and German, German and French, and to a lesser extent Russian and German, and Austrian and Russian forces. In 1915 attempts were again made by both sides to initiate an unofficial truce, but explicit, enforced orders by superior officers and localized artillery barrages redacted any widespread involvement.

Post-WWI the West has become bitter, cynical, narcissistic, and disillusioned, but these men did not live in our world. They lived in a world that had seen national movements unite entire peoples in Germany and Italy. In a world that had seen the world transform by industrialization, where progress seemed inevitable, and where hope could reside in the most despondent of places. Christmas is a time of remembering and celebration. This year, let us remember. Lest We Forget.

__

Agatha Tyche