The island of Japan essentially functioned in isolation for centuries before American naval expansion forced trade issues on the Japanese people. Despite the centuries of isolation and strict process of executing shipwrecked sailors that landed on their island, the Japanese proved remarkably successful in adapting the modernized industrial practices of nineteenth century Europe, and within fifty years, Japan, though still torn between the Samurai and farm dominated traditional lifestyle and new found industrial power, had successfully converted to a mechanized labor force and become the local East Asian power that successfully defeated Russia in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War.

The European infiltration of the East was not the first attempt at ideological conscription the Japanese faced through history. Confucianism and Taoism both entered Japan from China; Buddhism spread into Japan over time as well. These religions never gained full strength within Japan and remained philosophical

or sociological theories and practices.

The actual Japanese-based religion did not get named until other religions began to enter the islands. Shintoism is an unusual religion around the world because there is no historical founder that introduced the belief structure. This sets it apart from other Eastern religions that gained followers in Japan as well as the major world religions of Christianity's Jesus and Islam's Muhammad. Also peciliar to Shintoism is that the religion does not offer universal claims of acceptance or involvement for all people. Shintoism is the religion of and intended only for the people and culture of Japan.

The religion is based on kami ("what is worshiped") which can be objects, people, events, or ideas with shrines dedicated for such things as mountains, war memorials, and successful harvests. Kami is used in specific contexts when referring to shrine dedications. Ancient documents declare that there are "eight million kami," but the large number merely indicates that kami are too numerous to count and that many things can be worshiped.

The Japanese people attend shrines for various occasions to seek help, offer praise, or give celebration - of which the largest and most popular is the annual new year festival that many of the Japanese participate in.

Despite the thousands of years of Shintoism in Japan, the reestablishment of the Japanese Emperor and the establishment of a more organized Shinto religion distressed Americans during the occupancy of Japan post-WWII. Although the emperor never explicitly called for a state-sponsored state religion, Americans unfamiliar with the Japanese saw the mass-involvement as evidence of state sponsored religion. By December 1945, Emperor Showa announced himself not eligible to be an object of worship and "denounced" the state sponsorship of Shintoism. As a result of the privatization of shrines, Shintoism has become a type of religious corporation in modern Japan.

Regardless of modern influences, economic pressures, political renouncements, or cultural changes, Shintoism is what the Japanese believe as it has always been. Through two and a half millenia, the Shinto arches have stood in Japan as a symbol of the strength of the Japanese people and have outlasted emperors, wars, invasions, and natural destruction. Shintoism is not just the religion of Japan or the beliefs of its island people. Shintoism is Japan.

__

Agatha Tyche

An analysis of my small corner of the world. Bibliography sources available upon request.

26.7.14

15.7.14

Oppression

Situated near the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa with strong religious ties to the Byzantine Empire and Greek Orthodoxy, Baltic Vikings, and the Asiatic Steppes, Russia is a land that merges East and West and is an anomaly of both. Some points of its history function as Eastern European while still others seem more Western Asiatic. Since Peter the Great's modernization of Russia in the eighteenth century, Russia has faced the West economically, militarily, and socially.

Ivan the Terrible's reign became foundational for Russia as it is today. His wars expanded the tsar's control along the entire Volga River and secured contacts with Central Asia. He also cemented power in the hands of the tsar, not the aristocratic boyars, by instituting land reforms, heavy taxes on the rich, and giving high governmental positions to lower class subjects. Perhaps the most famous examples of Ivan's fabled "terribleness" was the institution of the Oprichinina (1565-1572), the secret police, who answered directly to the king and could raid villages and kill nobility with impunity. These implementations stagnated the unadministered country and led to a period of significant instability following the death of Ivan the Terrible in 1584.

By 1613 the Russian populace had rallied around a new tsar of the Romanov family and expelled all foreign rulers from their land. This stability lead to the expansion of bureaucratic rule that organized and controlled all governmental interests. A consequence of this increased state control greatly curtailed peasant migrations who, by 1649, were no longer allowed to leave their landlord or homeland.

Despite this limitation on mobility on the serfs, Western influences grew through the acquisition of Ukraine and other western lands, and the ideological hold of the bureaucratic elite over the peasant class wavered. Peter the Great brought Russia into step with the great powers of Enlightened Europe during his reign in the early eighteenth century by political and scientific modernization.

As the Russian empire expanded, so did the powers of the tsarist autocracy. Owning a much larger percentage of land and being in power over other religious leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church gave the emperor unequaled power within his realm. No popular resistance challenged the accumulation of the tsarist powers, and many famous Russians, including Dostoyevsky, and many Russians believed that the might of the Russian Empire depended solely on strength and power of the tsar. Political blunders and military disasters were often blamed on the aristocracy and bureaucracy of the empire.

From at least the early 1800s, the segments of society that resisted the repressive power of the tsarist regime were sent to Siberia to join work camps and to isolate and reduce the possible spread of dissent. Nicholas I (1825-55) put down the Decembrist Revolt that sought to introduce a constitutional monarchy to the Russian Empire after the military's exposure to Western liberalism during the Napoleonic Wars. In place of a constitutional monarchy, Nicholas I implemented "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality" as his governing ideology and sent secret police to enforce anti-monarchical censorship around the empire.

The nineteenth century revealed Russia's potential strength as during the Napoleonic wars but hinted at the flaws of stifled innovation as the nation was torn by revolts mid century. Aside from the top-down emancipation of the serfs in 1861 by Tsar Alexander II, few freedoms were granted to the populace compared to the much more liberal Western powers. Nonetheless, later in the nineteenth century, Alexander III returned to Nicholas I's autocratic policies and sought to isolate his empire to reverse the effects of the West in a process called Russification.

The taste of reform and freedom that 1861 gave to the peasants coupled with reports of reforms going on throughout Europe led to political turmoil and social unrest that intensified throughout the nineteenth century, imposed reform in the 1905 revolution, and ultimately overthrew the tsarist government in 1917. As Lenin then Stalin instituted a communist state, control over dissidents, propaganda, and state confiscations led to the development of a powerful secret police. Dissenters and suspected dissenters of the government were sent to the now infamous work camps known as gulags scattered throughout Russia. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Russia became a federal state that has adjusted to the balance of its communist past with capitalist economic reforms.

Despite the by-Western-standards oppressive history of the tsars and Secretary Generals of the last half-millennium, the Russian people remain energetic, passionate, and powerful. The Russian people slug through adversary and opposition with an ease that rival nations envy. Russia is resource rich, diverse, and fearsome in both its geography and its people.

No other people in the world can maintain a multi-continental empire for five centuries through world wars, revolts, political collapse, economic flouderings, and the uncertainty of the modern age with the respectable success of the Russian people who will always outlast winter and persist in conquering.

__

Agatha Tyche

Ivan the Terrible's reign became foundational for Russia as it is today. His wars expanded the tsar's control along the entire Volga River and secured contacts with Central Asia. He also cemented power in the hands of the tsar, not the aristocratic boyars, by instituting land reforms, heavy taxes on the rich, and giving high governmental positions to lower class subjects. Perhaps the most famous examples of Ivan's fabled "terribleness" was the institution of the Oprichinina (1565-1572), the secret police, who answered directly to the king and could raid villages and kill nobility with impunity. These implementations stagnated the unadministered country and led to a period of significant instability following the death of Ivan the Terrible in 1584.

By 1613 the Russian populace had rallied around a new tsar of the Romanov family and expelled all foreign rulers from their land. This stability lead to the expansion of bureaucratic rule that organized and controlled all governmental interests. A consequence of this increased state control greatly curtailed peasant migrations who, by 1649, were no longer allowed to leave their landlord or homeland.

Despite this limitation on mobility on the serfs, Western influences grew through the acquisition of Ukraine and other western lands, and the ideological hold of the bureaucratic elite over the peasant class wavered. Peter the Great brought Russia into step with the great powers of Enlightened Europe during his reign in the early eighteenth century by political and scientific modernization.

As the Russian empire expanded, so did the powers of the tsarist autocracy. Owning a much larger percentage of land and being in power over other religious leaders of the Russian Orthodox Church gave the emperor unequaled power within his realm. No popular resistance challenged the accumulation of the tsarist powers, and many famous Russians, including Dostoyevsky, and many Russians believed that the might of the Russian Empire depended solely on strength and power of the tsar. Political blunders and military disasters were often blamed on the aristocracy and bureaucracy of the empire.

From at least the early 1800s, the segments of society that resisted the repressive power of the tsarist regime were sent to Siberia to join work camps and to isolate and reduce the possible spread of dissent. Nicholas I (1825-55) put down the Decembrist Revolt that sought to introduce a constitutional monarchy to the Russian Empire after the military's exposure to Western liberalism during the Napoleonic Wars. In place of a constitutional monarchy, Nicholas I implemented "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality" as his governing ideology and sent secret police to enforce anti-monarchical censorship around the empire.

The nineteenth century revealed Russia's potential strength as during the Napoleonic wars but hinted at the flaws of stifled innovation as the nation was torn by revolts mid century. Aside from the top-down emancipation of the serfs in 1861 by Tsar Alexander II, few freedoms were granted to the populace compared to the much more liberal Western powers. Nonetheless, later in the nineteenth century, Alexander III returned to Nicholas I's autocratic policies and sought to isolate his empire to reverse the effects of the West in a process called Russification.

The taste of reform and freedom that 1861 gave to the peasants coupled with reports of reforms going on throughout Europe led to political turmoil and social unrest that intensified throughout the nineteenth century, imposed reform in the 1905 revolution, and ultimately overthrew the tsarist government in 1917. As Lenin then Stalin instituted a communist state, control over dissidents, propaganda, and state confiscations led to the development of a powerful secret police. Dissenters and suspected dissenters of the government were sent to the now infamous work camps known as gulags scattered throughout Russia. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, Russia became a federal state that has adjusted to the balance of its communist past with capitalist economic reforms.

Despite the by-Western-standards oppressive history of the tsars and Secretary Generals of the last half-millennium, the Russian people remain energetic, passionate, and powerful. The Russian people slug through adversary and opposition with an ease that rival nations envy. Russia is resource rich, diverse, and fearsome in both its geography and its people.

No other people in the world can maintain a multi-continental empire for five centuries through world wars, revolts, political collapse, economic flouderings, and the uncertainty of the modern age with the respectable success of the Russian people who will always outlast winter and persist in conquering.

__

Agatha Tyche

29.6.14

Packaged

The British Commonwealth of Nations celebrates Boxing Day on December 26, the day after Christmas. There is no known origin for the holiday, but theories abound from the Roman-early Christian period to the Medieval to the Renaissance. It coincides with the feast of St. Stephen and also has religious undertones as the second day of Christmas. During the World Wars, Canada, Australia, and several other British colonies, protectorates, and sister nations sent supplies to England for the war effort.

Begun as a day to give gifts to strangers, Boxing Day continues to be a day of giving to people with less, but recent decades have challenged this past. Canadian Boxing Day has become an enormous retail day similar to Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving, in the United States.

There is another way to share surplus goods with strangers: actions, words, care.

What is a box? Whatever you need a box to be. The box can be a mindset, a paradigm, a method, a worldview, a theory, a mood, a method or approach. It can be freedom, hope, exploration, discovery, happiness, desire, creativity, love, a dream, a goal. The box is anything, good or bad, that can be passed on to others. It can be lost, desperate, inevitable or definite, confident, enduring. Sometimes a box is only a weak, flimsy cardboard container that cannot withstand use, weather, or time. Sometimes a box is a secret place of gilded mahogany that secures the most valuable items in the world.

Mankind is curious, creative, and ingenious. We create, alter, expand, and build like no other creature. Perspective is key. A box is more than something to transport, store, or hold items. A box can be permanent or temporary, plain or adorned.

Think of a box from the view of a cat. Hide in it, hop on it, learn its crevices, and use it for a variety of purposes. Move forward with gifts; don't store your burdens up like curses. Be strategic, flexible, adaptable, caring, and selfless.

It all depends on you see the box.

__

Agatha Tyche

Begun as a day to give gifts to strangers, Boxing Day continues to be a day of giving to people with less, but recent decades have challenged this past. Canadian Boxing Day has become an enormous retail day similar to Black Friday, the day after Thanksgiving, in the United States.

There is another way to share surplus goods with strangers: actions, words, care.

What is a box? Whatever you need a box to be. The box can be a mindset, a paradigm, a method, a worldview, a theory, a mood, a method or approach. It can be freedom, hope, exploration, discovery, happiness, desire, creativity, love, a dream, a goal. The box is anything, good or bad, that can be passed on to others. It can be lost, desperate, inevitable or definite, confident, enduring. Sometimes a box is only a weak, flimsy cardboard container that cannot withstand use, weather, or time. Sometimes a box is a secret place of gilded mahogany that secures the most valuable items in the world.

Mankind is curious, creative, and ingenious. We create, alter, expand, and build like no other creature. Perspective is key. A box is more than something to transport, store, or hold items. A box can be permanent or temporary, plain or adorned.

Think of a box from the view of a cat. Hide in it, hop on it, learn its crevices, and use it for a variety of purposes. Move forward with gifts; don't store your burdens up like curses. Be strategic, flexible, adaptable, caring, and selfless.

It all depends on you see the box.

__

Agatha Tyche

28.6.14

"It is nothing."

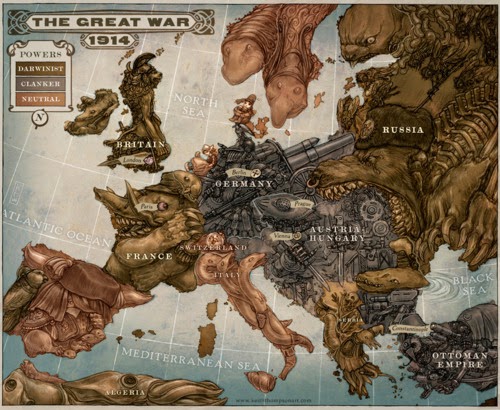

The causes of the Great War are both many and none. While the revenge the Austrian-Hungary Empire sought on Serbia for the assassination of its heir is noted as the catalyst of the incomprehensible violence of the World War I, the war was long in coming. The rivalries of the great European powers in the nineteenth century created festering wounds that eventually ripped Europe apart. Tensions between France and Prussia, Britain and Prussia, and Austria-Hungary and Russia all combined for tense diplomatic relations that definitively began the destruction of global European hegemony.

On Saturday, June 28, 1914 at 4:00pm during a visit to Serbia, Archduke Francis Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the throne of Austria-Hungary, and member of the House of Habsburg, was assassinated by Gavrilo Princep, a Serbian nationalist and member of the anarchist group the Black Hand. The death of one man became the death of millions in a four year war that broke the world.

__

Despite several failed attempts on his life earlier that day, the archduke visited a hospital to see wounded from a bombing attempt on his life. When it seemed that the stress of the day was nearly over, the motorcade of Francis Ferdinand and his wife crossed paths with another assassination attempt, this one successful. Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, wife of Francis Ferdinand, died on the journey to the governor's house for medical treatment. The last words of the archduke were, " Sophie, Sophie! Don't die! Live for our children!" then with a pause, "It is nothing." which was echoed several times.

"It is nothing," perfectly sets up the cause for Europe's subsequent destruction. Slaughtering itself for nationalist pride above any logical reason, the Archduke Francis Ferdinand seemingly predicted the pointlessness of the next four years.

Exactly a century after this pivotal moment, the pre-World War world seems naive, ostentatious, and proud. That reflection is through the eyes of cynicism, despair, and death that for decades characterized the thoughts of the West.The two most deadly wars in history began over nothing but ended in a ritualistic suicide of the old world order.

Today, let us not celebrate death but somberly remember the pain, suffering, and pointless causes that wreak total war, total destruction, and total waste on the world. Let us do better.

Agatha Tyche.

28.5.14

Lepidoptera

History is like a butterfly.

Time is the body that directs the motions and holds the entity together. Its directions seem haphazard, but usually the destination is achieved with unpredicted ups and downs and being blown about in the wind.

History itself is the wings. As a whole, it is a beautiful, complex image that both confuses and awes. History is somewhat symmetrical and repetitious which is expressed by identical wing patterns. However, altered experiences age time differently and create the tatters on the wings of history that reveal the diversity of the past. History repeats but is not repetitious; it merely echoes the reverberations of time gone by.

As a whole, the story of history is fascinating as are butterflies.. Looking more closely, history, like a butterfly's wings, is composed of smaller pieces. The scales of a butterfly's wings are the individual stories of history from the starving struggle of a beggar to a desperate last stand or how a storm of the century instigated political policies for generations.

As a whole, the story of history is fascinating as are butterflies.. Looking more closely, history, like a butterfly's wings, is composed of smaller pieces. The scales of a butterfly's wings are the individual stories of history from the starving struggle of a beggar to a desperate last stand or how a storm of the century instigated political policies for generations.

Once the shimmering beauty of the scales is rubbed off, the original pattern becomes faint and hard to notice just like lost historical accounts cloud the past.

The last similarity involves both external and internal influences. History is influenced by time just as the geography is by climate. While man is able to choose his own path, nature and precedent narrow his maneuver's possibilities. A butterfly is buffeted in the wind but can choose to land anywhere it likes while flitting about in the tempest's current.

Beauty is all around from the big picture to graphic details. Triumph to tragedy, impoverished to impossible, and rare to repetitious, life and history inevitably march on.

Beauty is all around from the big picture to graphic details. Triumph to tragedy, impoverished to impossible, and rare to repetitious, life and history inevitably march on.

__

Agatha Tyche

Agatha Tyche

22.5.14

The Pasts' Best Hopes

The process of living is filled with change. Nothing remains the same, but all change is faced by opposition. Nature resists reconstruction of its surfaces, and in direct opposition to this reluctant transformation, humans constantly carve out, reshape, and innovate while striving to live the best possible life.

Anthropological accomplishments pass on through history to motivate, inspire, and stand as a testament to the strength of humanity. These innovators of stable, prosperous, and painful change revolutionized their worlds and served to shape the world today both through their decisions as well as the inspiration of their legacies.

The establishment of an empire is much easier than its consolidation and maintenance. Many ancient empires failed to live on past the second or third generation from the founder. Hammurabi understood the importance of governance in an empire and established the first known written law code. Even today his face decorates many courts because of his recognition that justice is instrumental to the foundation of any government.

Russia is a geographically large nation, but being outside of the cultural centers of Western Europe and China, she has often struggled to stay with the leading technological edge despite her massive resources. Csar Peter the Great began the modernization of Russia's vast lands in the early eighteenth century. No man can live forever, and after his death, Russia began to slip from its perch near the forefront of the world. The modernization craze did not become recognizably complete until Stalin's efforts from the 1930s-1950s when he transformed the military and industry of a large but poor population into one of the greatest powerhouses in the world.

Meji the Great transformed the Empire of Japan from a samurai ruled and agriculturally dependent island into the steel war machine that controlled Asia and dominated the Pacific by the mid-twentieth century after only a few decades of dramatic change. The industrial revolution sacrificed traditional Japanese culture in order to maintain self-governance, and with the incredible speed of this transformation, Meji saw Japan succeed in that goal.

Frederick the Great established the Prussian military's high standards of performance, capable nobles, and cultural fluency. He sowed the seeds of union as Prussian lands, once scattered and unconnected, became a cohesive kingdom that called the German peoples to unite once again into a single, great nation.

Otto von Bismarck used his talents in political maneuverings and Moltke's military organization to defeat several nations, promote economic growth, and consolidate centuries-divided kingdoms into a powerful Germany.

Alfred the Great defended his English kingdom against the Vikings, Saladin staved off the Christian invaders of Jerusalem, Thutmose III expanded Egypt's boundaries to previously inconceivable extents, and Napoleon began the modern European age of nationalism, total war, and propaganda-fueled domestic support. Throughout time and place, great challenges have revealed the greatest of man's potential. Nothing stays stable, nothing is permanent, and nothing lasts forever, but as long as mankind is able to push forward, reach farther, and never surrender, he shall persist, thrive, and inspire.

__

Agatha Tyche

Anthropological accomplishments pass on through history to motivate, inspire, and stand as a testament to the strength of humanity. These innovators of stable, prosperous, and painful change revolutionized their worlds and served to shape the world today both through their decisions as well as the inspiration of their legacies.

The establishment of an empire is much easier than its consolidation and maintenance. Many ancient empires failed to live on past the second or third generation from the founder. Hammurabi understood the importance of governance in an empire and established the first known written law code. Even today his face decorates many courts because of his recognition that justice is instrumental to the foundation of any government.

Russia is a geographically large nation, but being outside of the cultural centers of Western Europe and China, she has often struggled to stay with the leading technological edge despite her massive resources. Csar Peter the Great began the modernization of Russia's vast lands in the early eighteenth century. No man can live forever, and after his death, Russia began to slip from its perch near the forefront of the world. The modernization craze did not become recognizably complete until Stalin's efforts from the 1930s-1950s when he transformed the military and industry of a large but poor population into one of the greatest powerhouses in the world.

Meji the Great transformed the Empire of Japan from a samurai ruled and agriculturally dependent island into the steel war machine that controlled Asia and dominated the Pacific by the mid-twentieth century after only a few decades of dramatic change. The industrial revolution sacrificed traditional Japanese culture in order to maintain self-governance, and with the incredible speed of this transformation, Meji saw Japan succeed in that goal.

Frederick the Great established the Prussian military's high standards of performance, capable nobles, and cultural fluency. He sowed the seeds of union as Prussian lands, once scattered and unconnected, became a cohesive kingdom that called the German peoples to unite once again into a single, great nation.

Otto von Bismarck used his talents in political maneuverings and Moltke's military organization to defeat several nations, promote economic growth, and consolidate centuries-divided kingdoms into a powerful Germany.

Alfred the Great defended his English kingdom against the Vikings, Saladin staved off the Christian invaders of Jerusalem, Thutmose III expanded Egypt's boundaries to previously inconceivable extents, and Napoleon began the modern European age of nationalism, total war, and propaganda-fueled domestic support. Throughout time and place, great challenges have revealed the greatest of man's potential. Nothing stays stable, nothing is permanent, and nothing lasts forever, but as long as mankind is able to push forward, reach farther, and never surrender, he shall persist, thrive, and inspire.

__

Agatha Tyche

21.4.14

The End of the World

Most religions have apocalyptic scenarios in their doctrines. None of the world empires of the past have existed at their zenith of influence and might forever and inevitably succumb to change whether internally, externally, or an alloy of those changes. An unique comparative analysis can be examined when comparing the eschatological hope-fears of the Christian Byzantium Empire and the enthusiastic vigor of the newer Islamic forces.

An extension of the historical Roman Empire, Byzantium, with its capital of Constantinople, remained strong well into the tenth century if at only a shadow of its former power. The Judeo-Christian belief system upon which the Eastern Roman Empire was founded under Constantine took the promise of Jesus' return "soon" seriously and strove to set up a Christian world empire to begin Jesus' Millennial Reign on earth. This belief motivated the Byzantine's to expand and conquer, especially the areas around Jericho and the Holy Land.

However, the quick rise of the fundamentally oppositional Islamic power immediately and dramatically reduced the dominating capabilities of the Byzantines. The Byzantine Empire was not unfamiliar with the tides of fortune having long weathered bankruptcy, civil unrest, plague, and military defeat. Initially, even as the empire's strength waned, hope burgeoned, especially in the outskirts of Constantinople's provinces. A variety of groups and belief systems viewed their Roman-founded empire as immortal as the phoenix that must suffer defeat to be renewed to full prominence again.

On the other side of the spectrum, the new Muslim armies expanded furiously with their own religious urgency in conquering the world because of the basic teaching's of Muhammad warning that the world would end and God would judge all.

Cambridge University Press, 2007), 330.

Byzantium Christendom and the Islamic Empire had the end of the world to spur their conquests; thus, both sides of a centuries long war struggled to convert the world before the end. These two mighty empires used religion to mutual self-destruction.

In the case of Byzantium, European Crusaders did as much to destroy Constantinople as the Islamic forces. Centuries of war, contraction of governed land by church officials, and reduced tax revenue wore out the Eastern Roman Empire. The Islamic armies fractured under diverging sects and local governors over their vast holdings. Essentially both empires crippled themselves enough for an outside force to have the final impact. The Arab-based Muslim world shifted as Asian Turks took the reigns of the empire, and the Byzantines eventually fell to these Islamic-modified Turks as well.

In the end both regimes got what they long expected though perhaps neither side predicted the "apocalypse" to be of their empire, not the world. However and whenever man's world ends has been the focus of legends, tales, and religions for millenia. Since we can neither know the day of our own death nor the death of the world, strive to do all you can in the time given to consistently carry out your beliefs and improve upon the world that we do have for as long as we have it.

__

Agatha Tyche

An extension of the historical Roman Empire, Byzantium, with its capital of Constantinople, remained strong well into the tenth century if at only a shadow of its former power. The Judeo-Christian belief system upon which the Eastern Roman Empire was founded under Constantine took the promise of Jesus' return "soon" seriously and strove to set up a Christian world empire to begin Jesus' Millennial Reign on earth. This belief motivated the Byzantine's to expand and conquer, especially the areas around Jericho and the Holy Land.

However, the quick rise of the fundamentally oppositional Islamic power immediately and dramatically reduced the dominating capabilities of the Byzantines. The Byzantine Empire was not unfamiliar with the tides of fortune having long weathered bankruptcy, civil unrest, plague, and military defeat. Initially, even as the empire's strength waned, hope burgeoned, especially in the outskirts of Constantinople's provinces. A variety of groups and belief systems viewed their Roman-founded empire as immortal as the phoenix that must suffer defeat to be renewed to full prominence again.

Overall there seemed to be a fairly popular train of thought that imperial redemption and renewal would start on the outskirts of the Byzantine Commonwealth and be consummated in Constantinople and/or Jerusalem. At least in part this tendency could be explained by the belief that the empire itself needed a renewal, its sacred vitality no longer strong enough to guarantee the empire's triumphant universalism. The power of renewal could no longer be found within Constantinople but outside of it. The shift of focus. of imperial sacred geography from the imperial center to the periphery sought to restore the vitality of mythical Byzantium through the inversion of established canons of imperial sacred space. In the situation in which the imperial center lost its strength, once-peripheral parts of the empire claimed this strength for themselves, positioning themselves as legitimate successors of Constantinople.1

1 Alexei Sivertsev. Judaism and Imperial Ideology in Late Antiquity (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University

Press, 2011), 214.

As the years wore on without providing a great return of Byzantine might, defeatism set into the culture, and the once proud armies of the Eastern Roman Empire called upon the Franks for military aid. The mighty Christian empire was set to fall.

What drove Muhammad and his armies to conquer is a subject of deepest controversy . . . it is clear that the common Late Antique themes of universalism and apocalypticism shaped both his message and his method. A significant portion of the Qur'an addresses the Apocalypse (the Last Day, the Overwhelming Event) when God the righteous judge would return and set the whole world to right. Believers were enjoined to a Holy War to prepare themselves and the world for the impending day of reckoning. Muhammad's last recorded speech admonished that 'Muslims should fight all men until they say "There is no god but God."' The goal seems to have been to build a universal righteous community - a melding of Late Antique monotheism with dynamics drawn from deep in the Age of Ancient Empires.22 Eric Cline and Mark Graham. Ancient Empires: From Mesopotamia to the Rise of Islam (Cambridge, UK:

Cambridge University Press, 2007), 330.

Byzantium Christendom and the Islamic Empire had the end of the world to spur their conquests; thus, both sides of a centuries long war struggled to convert the world before the end. These two mighty empires used religion to mutual self-destruction.

In the case of Byzantium, European Crusaders did as much to destroy Constantinople as the Islamic forces. Centuries of war, contraction of governed land by church officials, and reduced tax revenue wore out the Eastern Roman Empire. The Islamic armies fractured under diverging sects and local governors over their vast holdings. Essentially both empires crippled themselves enough for an outside force to have the final impact. The Arab-based Muslim world shifted as Asian Turks took the reigns of the empire, and the Byzantines eventually fell to these Islamic-modified Turks as well.

In the end both regimes got what they long expected though perhaps neither side predicted the "apocalypse" to be of their empire, not the world. However and whenever man's world ends has been the focus of legends, tales, and religions for millenia. Since we can neither know the day of our own death nor the death of the world, strive to do all you can in the time given to consistently carry out your beliefs and improve upon the world that we do have for as long as we have it.

__

Agatha Tyche

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)