The United States' global success in the second half of the twentieth century is a direct result of the way the nation developed through the stages of history from native-filled woods to terrifying nuclear arsenals. The seeds of independent government started early in the history of the nation both with written forms like the Mayflower Compact as well as in the spirit of settlers that left civilization to live in the wilderness and establish their own societies. Eventually this spirit of independence culminated in the American War for Independence (1776-1783) which resulted in a loose confederation of states eventually bound under the Constitution that remains the living foundation for the United States.

The Founding Father of the United States, George Washington, used his military experience and political knowledge to help establish the Constitution and spread its rule to the thirteen states. As a military leader popular with the American public and respected among his aristocratic peers, Washington was unanimously elected president. George Washington's two terms as president set many precedents for other American leaders to follow including the establishment of a presidential cabinet system, the amended clause "So help me God" when swearing the oath of office, and the retirement from political service after leading the federal executive branch. One of the last cornerstones of his presidency was his Farewell Address in which he stated his wishes for the country, warned of dangers foreseen, and advised on potential calamities from certain courses of action. Since Washington, other presidential resignation speeches have become famous, especially Dwight D Eisenhower's 1960 speech regarding the dangers of the military-industrial complex.

George Washington's 1797 Farewell Address encompasses a vast array of topics that the fledgling nation faced or would face in the future, but several points have become hallmarks to Washington's wisdom and foresight. At the time of Washington's writing, the United States was a decade old, militarily weak, and almost entirely reliant on British trade while favoring the political support of France. Referencing his career in the military both in the Seven Years War (The French and Indian War; 1756-1763) and the American Revolution, Washington had observed the unintended effects of European alliances and the social costs of war: death, taxes, and political tension.

With this lifetime of military and political experience in perspective, Washington stated in his Farewell Address cautions against forming peacetime alliances with European nations since that would draw limited American resources into repetitious conflicts across the seas. Although unheeded, Washington's second great caution was to avoid political bipartisanship since a dual-party political system would unnecessarily divide the brilliance of America's leaders into oppositional camps. A last great caution was that America should keep its leaders to the highest moral requirements because moral resilience gave American society its strength (Tocqueville, 1835).

Emphasized throughout the letter is the preservation of the new national unity. As portrayed by the first American political cartoon by Benjamin Franklin in the Seven Years War "Join or Die." The threat of separation by selfish states' interests alarmed the Founding Fathers from the earliest years and remained one of the largest obstacles to unity even past the American Civil War.

George Washington has had the respect of his American brethren for two and a half centuries. His words have dictated foreign policy for generations, stilled momentary passions, and created an introspective narrative to America's history and actions. His passion for his homeland stirred him to oust British Imperial rule, set precedent for peaceful power transitions, and caution his beloved nation of dangers. Establishing insight for American conduct in both domestic and international affairs, Washington sought to rely on the "Common Sense" of the American people to elect leaders that would seek fair treatment of its citizens and impartial, commercial relations with other nations around the world.

Reflections on pivotal political decisions in American history since the writing of the Washington's Farewell Address reveal the respect for the Founding Fathers the people and leaders of America have engendered. Those cautions created a strong influence on foreign and domestic policies throughout the past two centuries. America avoided European wars in the nineteenth century and only made its first peacetime alliance with the formation of NATO after World War II. While the moral core has remained intact, the fickle will of the people has caused changes to the republic established by the Founding Fathers. Though strained by the Civil War, the Progressive Movement, and Social Services, the republic endures. The only major piece of caution wholly rejected by America is the formation of a two party system which established itself immediately after Washington and continues to basally affect the governance of the country today. Though fundamental for the birth, development, and rise of a twentieth century superpower, the lessons of Washington's Farewell Address were heeded by citizens, Congress, and cabinets throughout the history of the United States of America but have been increasingly ignored by the passage of time and the rise of new generations.

In this American tradition of reflection before resignation, I offer some closing words of hope and advice that my perspective has cultivated. Through four and a half years, I have used themes of science and history to address virtues, remember forgotten events, and uncover the motivation of individuals from all parts of recorded history, but all things end. Since every man of greatness has died, every grand empire has faded, and every absolute, undeniable reality has been altered, it may seem foolish to attempt to embody resilience for values of personal worth, but the world is not shaped by the decisions of one person. No, the world is shaped by a culmination of individuals pressing toward a goal, regardless of motivation, just as Thomas Hobbes described in Leviathan (1651). Unity is the strength of man, but that unity will only persist by the quality and endurance of each individual. Education, context, and awareness establish the paramount tools in embodying your personal and societal values. Watch, think, and decide to determine action just as the most successful leaders of history and science have. Learn from the past to improve the future.

__

Agatha Tyche

Wyyes: microcosm

An analysis of my small corner of the world. Bibliography sources available upon request.

31.12.16

24.12.16

Monopole

In particle physics investigations with electromagnetism, a monopole is a magnet that can be distinctly separated into individual poles instead of the normal dipolar magnet. While many physicists, especially supporters of string theory, tout the existence of monopoles, it remains unconfirmed in nature. The physicist inquiry only deals with innate matter of the universe but rejects the study of more complex objects. If monopoles could theoretically exist in particles across the universe, then complex agents like people and political affiliations should exemplify this scientific claim easily.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) split the United States into two camps concerning either states' rights or slavery. The cost of that deliberation was four years, 650,000 lives, and an irreparable rent in American identity. Regardless of the fundamental cause of the war, the ideological divide of Congress reflected in the eventual allegiance of each state. In every conflict a line must be drawn, and this division formed along the border states between the free, pro-Union North and pro-slavery, rebel South. The collision between the Northern industrial might and Southern fervor energies clashed along that border with enough blood and horror to rename towns.

The border states had the most to lose in this conflict. The support of their populations was divided, the requisition of their resources was hounded, and the pain of the war stretched through their lands.

Missouri had long been at the heart of the slavery controversy in the United States with politicking creating the Missouri Compromise in 1820. Kentucky attempted to remain neutral but eventually sided with the Union in attempts to stave off invasion by a Southern general. Virginia voted to secede, but by 1863 the western portion of the state seceded from Virginia and was voted back into the Union as West Virginia. With the anti-Union antagonism in Baltimore, Maryland reached a crescendo in riots that killed a dozen people and solidly pitted the city legislature and much of the state in opposition to Federal military actions.

One of the most blatant actions taken by the Federal (Union) government involved securing the support of the border state Maryland. Because the federal government resided in Washington D.C. across the river from the Confederate Virginia, Lincoln ordered federal troops to secure Baltimore, its railroad connections, and, by whatever means necessary, the support of the state legislature. While Maryland officially voted to stay in the Union, it did so while occupied by 75,000 Federal troops and a third of its legislature in prison with suspended rights. Lincoln's Army forced Maryland to stay in the Union to protect Washington D.C. Conscription efforts in Maryland forced most of those recruits to serve in far-flung theaters of war to avoid desertion to the South. Though reliable records are difficult to ascertain because of the poor record keeping of the South, an estimated thirty-seven percent of all Maryland Civil War veterans fought for the Confederacy.

Following the Civil War the culture of the border states evolved naturally compared to the suppression of the Solid South. Native Southern Whites resented the Northern carpetbaggers and freed blacks but remembered their solidarity to the Democrat political party. Since the war Missouri, Kentucky, and much of West Virginia realigned cultural values toward the South, rejecting the city richness of many of the Northern states.

One border state, however, is still refused any positive association or cultural affiliation from either side of the war. The South rejects Maryland because it sided its support and resources to the Union; the North ignores Maryland because its spirit longed for the rebel cause.

Maryland is the American monopole that takes on the attributes desired from certain perspectives. The South has long resented the War of Northern Aggression, and the North has not forgotten the resentment created from coercive Union. Maryland has suffered substantially from that estrangement and bitterness. The bloodiest day in American history, September 17, 1862, had 22,000 casualties and splattered its blood on Maryland soil.

In the century and a half since the American Civil War, Maryland has remained an unwanted reject among its counterpart states. The Northern States enjoy its trade and access to the nation's capitol, and the South appreciates its Chesapeake Bay Culture. In that time the Federal Government's powers and wealth have increased substantially, and those financial powers have allowed government officials to buy homes and lands in Maryland. The elite hierarchy resides in Maryland to escape the stress of the city, and the president's retreat is Camp David, in the foothills of Maryland.

The Civil War was bloody, and the border states soaked that blood in to reshape the nation. Maryland is the ostracized state that has been disowned by both North and South. A consolation prize for that rejection is the wealth of the reformed Federal Government which has made Maryland the richest state in the richest nation in the world, and it is still hated by all.

To readers around the world, as addressed in "Post Hekaton" in March, 2016, one more post is coming this month before the regular updates for this blog end. Writing efforts are being focused on a novel which has been in planning for six years. The blog may eventually be resurrected because the appeal of learning never diminishes.

I would like to send my thanks to the many of you that regularly read these clips of historical, political, scientific, and social thought with special thanks to regular readers in France, Portugal, Russia, and the United States.

__

Agatha Tyche

The American Civil War (1861-1865) split the United States into two camps concerning either states' rights or slavery. The cost of that deliberation was four years, 650,000 lives, and an irreparable rent in American identity. Regardless of the fundamental cause of the war, the ideological divide of Congress reflected in the eventual allegiance of each state. In every conflict a line must be drawn, and this division formed along the border states between the free, pro-Union North and pro-slavery, rebel South. The collision between the Northern industrial might and Southern fervor energies clashed along that border with enough blood and horror to rename towns.

The border states had the most to lose in this conflict. The support of their populations was divided, the requisition of their resources was hounded, and the pain of the war stretched through their lands.

Missouri had long been at the heart of the slavery controversy in the United States with politicking creating the Missouri Compromise in 1820. Kentucky attempted to remain neutral but eventually sided with the Union in attempts to stave off invasion by a Southern general. Virginia voted to secede, but by 1863 the western portion of the state seceded from Virginia and was voted back into the Union as West Virginia. With the anti-Union antagonism in Baltimore, Maryland reached a crescendo in riots that killed a dozen people and solidly pitted the city legislature and much of the state in opposition to Federal military actions.

One of the most blatant actions taken by the Federal (Union) government involved securing the support of the border state Maryland. Because the federal government resided in Washington D.C. across the river from the Confederate Virginia, Lincoln ordered federal troops to secure Baltimore, its railroad connections, and, by whatever means necessary, the support of the state legislature. While Maryland officially voted to stay in the Union, it did so while occupied by 75,000 Federal troops and a third of its legislature in prison with suspended rights. Lincoln's Army forced Maryland to stay in the Union to protect Washington D.C. Conscription efforts in Maryland forced most of those recruits to serve in far-flung theaters of war to avoid desertion to the South. Though reliable records are difficult to ascertain because of the poor record keeping of the South, an estimated thirty-seven percent of all Maryland Civil War veterans fought for the Confederacy.

Following the Civil War the culture of the border states evolved naturally compared to the suppression of the Solid South. Native Southern Whites resented the Northern carpetbaggers and freed blacks but remembered their solidarity to the Democrat political party. Since the war Missouri, Kentucky, and much of West Virginia realigned cultural values toward the South, rejecting the city richness of many of the Northern states.

One border state, however, is still refused any positive association or cultural affiliation from either side of the war. The South rejects Maryland because it sided its support and resources to the Union; the North ignores Maryland because its spirit longed for the rebel cause.

Maryland is the American monopole that takes on the attributes desired from certain perspectives. The South has long resented the War of Northern Aggression, and the North has not forgotten the resentment created from coercive Union. Maryland has suffered substantially from that estrangement and bitterness. The bloodiest day in American history, September 17, 1862, had 22,000 casualties and splattered its blood on Maryland soil.

In the century and a half since the American Civil War, Maryland has remained an unwanted reject among its counterpart states. The Northern States enjoy its trade and access to the nation's capitol, and the South appreciates its Chesapeake Bay Culture. In that time the Federal Government's powers and wealth have increased substantially, and those financial powers have allowed government officials to buy homes and lands in Maryland. The elite hierarchy resides in Maryland to escape the stress of the city, and the president's retreat is Camp David, in the foothills of Maryland.

The Civil War was bloody, and the border states soaked that blood in to reshape the nation. Maryland is the ostracized state that has been disowned by both North and South. A consolation prize for that rejection is the wealth of the reformed Federal Government which has made Maryland the richest state in the richest nation in the world, and it is still hated by all.

To readers around the world, as addressed in "Post Hekaton" in March, 2016, one more post is coming this month before the regular updates for this blog end. Writing efforts are being focused on a novel which has been in planning for six years. The blog may eventually be resurrected because the appeal of learning never diminishes.

I would like to send my thanks to the many of you that regularly read these clips of historical, political, scientific, and social thought with special thanks to regular readers in France, Portugal, Russia, and the United States.

__

Agatha Tyche

3.12.16

The West Man's Burden

Rudyard Kipling's dually famous and infamous poem "The White Man's Burden" speaks to a growing and strong American nation to reach forth like her European brethren and establish colonies abroad for the good of the far reaches of the world. Because of this poem as well as his outspoken support for British imperialist goals, Rudyard Kipling has long been recognized as one of the most vocal proponents of Western imperial expansionist ideals along with Cecil Rhodes. At the turn of the twentieth century, Europe controlled the world in every measurable aspect from population growth and military innovation to industrial production and scientific exploration. Because of this incredible gap of European possibility to the rest of the world, imperial ideals took hold during the conquest and colonization of the New World. By the time of the French Revolution, Europe was seeking the establishment of trade ports and settlements throughout Asia, and by the close of that same century, nearly all of the known world was either colonized by or allied with an imperial European nation.

Rudyard Kipling, who grew up in India, advocated for extending the imperialist agenda both toward nations friendly with Great Britain and to ensure the civilization of the rural, barbaric, pagan peoples of non-Europe. Kipling's and Europe's ideology for the colonization frenzy during the Age of Imperialism arose from the medieval practice of Christianizing Eastern and Baltic Europe in the medieval period. Europe was able to expand eastward because of more advanced military techniques, which, when combined with the lessons of New World colonization and naval development, allowed Europe to apply those technologies to the formation of empires. As British might reached the zenith of its capabilities, Kipling submitted his poem to one of the strongest proponents for American imperialism, Theodore Roosevelt, who became Vice President under William McKinley, a politician who built his career advocating American expansionist policies.

The process of successful colonization necessitates more advanced technology than currently possessed by the native populations. Technology allows the colonizers to travel, establish a presence, and fend off natural and human attempts to dislodge their encampment. As European nations established colonies around the world, foreign lands were secured through the oppressive application of technological innovation birthed in Europe since the Renaissance. Ocean going vessels, rifles, trains, machine guns, canned goods, and assembly-line industrial capacities allowed the imperialist goals of Europe to become reality.

Aside from the political goals that drove the conquest of the world, especially in the nineteenth century, there were as many motivations as advocates to interact with, subdue, and civilize the non-Western regions of the world. The Opium Wars between China and Great Britain exemplify the priority of economic might on a global scale to the real development of "civilization." Decades later, the slaughter of the Congolese people by the Belgians revealed no change in the approach or treatment of native peoples with regard to their non-economic existence. Despite the abusive, calloused use of native peoples as slaves for hard labor, the Christian Missionary movement, started in the early nineteenth century, sent waves of individuals to appeal to the eternal well-being of the souls of the natives. The techniques, methods, and interactions between these missionaries and the natives can be disputed, but several succeeded in establishing friendly relationships.

Colonization depended on control of the native peoples, but British over-extension in Africa resulted in the bloody Boer Wars in the 1890s. With realization of the limits of modern British capacities, Kipling hoped to activate British-friendly American sentiment for colonialism. The rhyme and meter of "The White Man's Burden" are attuned to an upbeat marching song calling sloven, cowardly men to better the world.

With the self-wrought destruction of the World Wars within Europe and the adoption of technological and industrial equipment throughout the rest of the world, Europe's Age of Imperialism weakened and collapsed completely midway through the twentieth century. The United States, a nation who resisted colonizing until the very end of the nineteenth century, maintained the technological innovation of its European heritage while avoiding the destruction of the World Wars which allowed it to express its own forms of imperial behavior into the early parts of the twenty-first century.

Disregarding the politically-weighted, racial imagery of the native African and Asian populations, the concept of the right of the powerful to control colonization was contested by intellectual, white elitists in America for decades prior to World War I. This resistance to capitalize on its technical superiority to the non-European world complemented American isolationism despite arguments for colonization's benefits for monetary gain, spiritual enlightenment, and furtherment of civilization .

Of all the causes that incited the imperialist agenda, the desire to industrialize and develop other cultures to the technological level of Europe largely succeeded after almost two centuries of occupation and turmoil. Those other cultures, from Brazil to South Africa and India to Indonesia, have progressed to compete with and even out-compete the European giants that introduced industrialized techniques of development. Given that many developing countries are advancing their economic production, most nations, arguably, have learned the lessons that European imperialism sought to teach them, though they are understandably not grateful for the repression and bloody strife those occupations created. If that is the case, the White Man's Burden should be nearly accomplished.

There are two main viewpoints of the Age of Imperialism and "The White Man's Burden." The acceptable viewpoint from the nineteenth century is that the Western Man sacrifices the luxuries of his home country to build railroads, extract resources, and educate the natives. Conversely, the acceptable viewpoint of late twenty and twenty-first centuries is that the white man oppressed, repressed, and enslaved local tribes for his own economic and political gains.

Comparing the mindset of Rudyard Kipling when he sent his poem to Theodore Roosevelt in 1899 with the events of the past one-hundred seventeen years, let us attempt to reconsider the words of the poem, "The White Man's Burden."

Agatha Tyche

Rudyard Kipling, who grew up in India, advocated for extending the imperialist agenda both toward nations friendly with Great Britain and to ensure the civilization of the rural, barbaric, pagan peoples of non-Europe. Kipling's and Europe's ideology for the colonization frenzy during the Age of Imperialism arose from the medieval practice of Christianizing Eastern and Baltic Europe in the medieval period. Europe was able to expand eastward because of more advanced military techniques, which, when combined with the lessons of New World colonization and naval development, allowed Europe to apply those technologies to the formation of empires. As British might reached the zenith of its capabilities, Kipling submitted his poem to one of the strongest proponents for American imperialism, Theodore Roosevelt, who became Vice President under William McKinley, a politician who built his career advocating American expansionist policies.

The process of successful colonization necessitates more advanced technology than currently possessed by the native populations. Technology allows the colonizers to travel, establish a presence, and fend off natural and human attempts to dislodge their encampment. As European nations established colonies around the world, foreign lands were secured through the oppressive application of technological innovation birthed in Europe since the Renaissance. Ocean going vessels, rifles, trains, machine guns, canned goods, and assembly-line industrial capacities allowed the imperialist goals of Europe to become reality.

Aside from the political goals that drove the conquest of the world, especially in the nineteenth century, there were as many motivations as advocates to interact with, subdue, and civilize the non-Western regions of the world. The Opium Wars between China and Great Britain exemplify the priority of economic might on a global scale to the real development of "civilization." Decades later, the slaughter of the Congolese people by the Belgians revealed no change in the approach or treatment of native peoples with regard to their non-economic existence. Despite the abusive, calloused use of native peoples as slaves for hard labor, the Christian Missionary movement, started in the early nineteenth century, sent waves of individuals to appeal to the eternal well-being of the souls of the natives. The techniques, methods, and interactions between these missionaries and the natives can be disputed, but several succeeded in establishing friendly relationships.

Colonization depended on control of the native peoples, but British over-extension in Africa resulted in the bloody Boer Wars in the 1890s. With realization of the limits of modern British capacities, Kipling hoped to activate British-friendly American sentiment for colonialism. The rhyme and meter of "The White Man's Burden" are attuned to an upbeat marching song calling sloven, cowardly men to better the world.

With the self-wrought destruction of the World Wars within Europe and the adoption of technological and industrial equipment throughout the rest of the world, Europe's Age of Imperialism weakened and collapsed completely midway through the twentieth century. The United States, a nation who resisted colonizing until the very end of the nineteenth century, maintained the technological innovation of its European heritage while avoiding the destruction of the World Wars which allowed it to express its own forms of imperial behavior into the early parts of the twenty-first century.

Disregarding the politically-weighted, racial imagery of the native African and Asian populations, the concept of the right of the powerful to control colonization was contested by intellectual, white elitists in America for decades prior to World War I. This resistance to capitalize on its technical superiority to the non-European world complemented American isolationism despite arguments for colonization's benefits for monetary gain, spiritual enlightenment, and furtherment of civilization .

Of all the causes that incited the imperialist agenda, the desire to industrialize and develop other cultures to the technological level of Europe largely succeeded after almost two centuries of occupation and turmoil. Those other cultures, from Brazil to South Africa and India to Indonesia, have progressed to compete with and even out-compete the European giants that introduced industrialized techniques of development. Given that many developing countries are advancing their economic production, most nations, arguably, have learned the lessons that European imperialism sought to teach them, though they are understandably not grateful for the repression and bloody strife those occupations created. If that is the case, the White Man's Burden should be nearly accomplished.

There are two main viewpoints of the Age of Imperialism and "The White Man's Burden." The acceptable viewpoint from the nineteenth century is that the Western Man sacrifices the luxuries of his home country to build railroads, extract resources, and educate the natives. Conversely, the acceptable viewpoint of late twenty and twenty-first centuries is that the white man oppressed, repressed, and enslaved local tribes for his own economic and political gains.

Comparing the mindset of Rudyard Kipling when he sent his poem to Theodore Roosevelt in 1899 with the events of the past one-hundred seventeen years, let us attempt to reconsider the words of the poem, "The White Man's Burden."

Take up the White Man's burden-- We took up the White Man's burden--

Send forth the best ye breed-- We sent out our only sons--

Go bind your sons to exile We wasted all our children

To serve your captives' need; As slaughter for their guns;

To wait in heavy harness, Our yolk's a heavy burden,

On fluttered folk and wild-- We tried to give it up--

Your new-caught, sullen peoples, Our nations tire and burn out,

Half-devil and half-child. We've drunk our bitter cup.

Take up the White Man's burden-- We took up the White Man's burden--

In patience to abide, Behind borders strove to hide,

To veil the threat of terror Remember 9/11

And check the show of pride; And check the show of pride;

By open speech and simple, With lies of revolutions,

An hundred times made plain We left on broken roads

To seek another's profit, But now our nation's troubles,

And work another's gain. All promise to implode.

Take up the White Man's burden-- We took up the White Man's burden--

The savage wars of peace-- The savage wars of greed--

Fill full the mouth of Famine Exploited earth's abundance

And bid the sickness cease; And silenced death's gross need;

And when your goal is nearest And when the goal was finished

The end for others sought, The end of empire sought,

Watch sloth and heathen Folly Watched civil war and arms deals

Bring all your hopes to nought. Bring all our work to nought.

Take up the White Man's burden-- We took up the White Man's burden--

No tawdry rule of kings, We overcame their kings,

But toil of serf and sweeper-- But still beat down their workers--

The tale of common things. For faster, cheaper things.

The ports ye shall not enter, Their ports have higher tariffs,

The roads ye shall not tread, Their roads have higher fees,

Go mark them with your living, Meanwhile our nation suffers,

And mark them with your dead. We rule from bended knees.

Take up the White Man's burden-- We took up the White Man's burden--

And reap his old reward: And reap our same reward:

The blame of those ye better, The scorn for those we labour,

The hate of those ye guard-- The fear of those we guard--

The cry of hosts ye humour The sounds of rifle fire

(Ah, slowly!) toward the light:-- Now killing off our aid:--

"Why brought he us from bondage, "Leave now our native cities,

Our loved Egyptian night?" Undo what you have made!"

Take up the White Man's burden-- We took up the White Man's burden--

Ye dare not stoop to less-- Give up your weariness--

Nor call too loud on Freedom Have men call out for Freedom

To cloak your weariness; To hide our sins against;

By all ye cry or whisper, With all our justice given,

By all ye leave or do, With all our Freedom spent,

The silent, sullen peoples The stronger, better peoples

Shall weigh your gods and you. Just want us to relent.

Take up the White Man's burden-- We took up the White Man's burden--

Have done with childish days-- It's time to lay it down--

The lightly proffered laurel, Esteem's not given freely,

The easy, ungrudged praise. The laurel leaves grow brown.

Comes now, to search your manhood What now is modern manhood?

Through all the thankless years What have our efforts won?

Cold, edged with dear-bought wisdom, Take up our load, ye Other!

The judgment of your peers! Embrace your native son.

With the financial turmoil within Europe in recent years including the 2008 Subprime Mortgage Crisis, Greek Financial Crisis, Refugee Crisis, and Brexit, European finance seems historically vulnerable while other non-Western nations are defining their own economic and political courses. The Asian Tigers are the strongest engines of growth in the world, even with China's uncertain transparency. The G20 membership further exemplifies the economic progress of non-European nations over the last century. While The European Union remains the largest trade conglomerate in the world, the rise of the Asian economies and the development of African resources stands as a testament to the ability and capacity of the "sullen peoples" of European colonialism. Whether this success stems from or in spite of colonialism, the European conquest of the world has revealed a burden that will never be put down.

___

14.11.16

Religious Monopoly

Syncretism and Henotheism

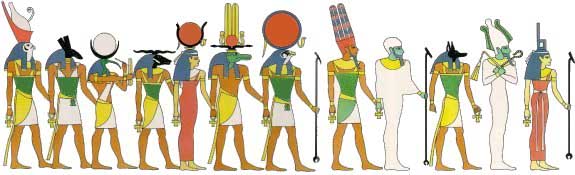

While true of Amun-Re and his two components, many other gods interacted with one another through merges, relations, and associations. Syncretism and henotheism were as integral to Egyptian religion as the sun since without ever-evolving associations, the religion would become gridlocked. Osiris is the most well documented case of henotheism because of his existence from the beginning of the Old Kingdom through the collapse of the Egyptian religion itself. Understanding the complexity of these associations between gods reveals the mindset that dictated the shifts of much of the ancient religion’s change through its existence. Foundational to the integration of gods deals with the universality of its acceptance. For example, all Egyptians believed that the underworld existed. Since all realms must have a king, Osiris successfully absorbed many others to become the sole king of the underworld throughout Egypt. Similarly, Ma’at dominated the definitions of truth, justice, and order while Nun represented doubt, chaos, and destruction.

The expanding influence of a god was usually directed by the religious stability of that deistic belief in concordance with the current dynasty. Local gods’ assertions to the forefront of political activity quickened universal acceptance among Egyptians. Local gods had very strong specific powers in that particular region while greater gods had widespread power but remained ineffectual in a particular region until association with local gods was secured. The few foreign gods that gained limited success in the delta regions of Egypt also employed this method like Anat-Hathor in the Third Intermediate Period.

The historic center of worship for a god was not always the origin as explained earlier with Amun. Most Egyptian gods had multiple functions that overlapped with other gods within that local region so that having three or four gods that served the same purpose was not uncommon. Classical Greek and Roman authors tried to specialize Egyptian god functions but oversimplified. The notable exceptions to this are Osiris, Isis, and Nephthys.

As the popularity of gods grew, triads formed within areas of heaviest influence. The largest organizational attempt in Egyptian history occurred under Amenhotep III with systematic reinterpretation of national deities to emphasize connections with Re. Two major categories resulted. The first, hybrids, resulted in a third god with a hyphenated name that combined the depictions of both gods. Instead of reducing the overall number of gods like henotheism, hybrids created a new god altogether. Sobek-Re combined the powers of the crocodile god with that of the sun; this new god’s largest worship base was Memphis, a stronghold of neither Sobek nor Re. The second method drew connections through associations. Thoth and Re both held baboons sacred and thus, the two gods were linked through this. The largest problem from this second method is that there was little consistency in depiction since physical attributes only revealed part of a god’s attributes. This caused the creation of the third god. Also, the greater the god and the more gods he absorbed, the more representations depicted. Re’s symbolism is extremely varied.

The process of syncretism resulted in the hyphenation of gods to show dual characteristics that provided two, three, or nine-fold strength. However, this often did not result in a more comprehensive, single god. Henotheism involved a blending of traits where one god obviously prevailed. This also occurred in two manners. If a greater god absorbed a lesser god, such as Osiris over Andjti, the inferior god completely disappeared with only reminiscent symbolism. To stave off this act, lesser gods could assume parts of a greater god as was widely done with sun gods and Re.

Gods are merged based on similar traits, depictions, and character. Sekhmet and Bastet, both cat goddesses, often merged because of their similarity in depiction and realm of worship. A partial statue now located in the British Museum of Nature History contains a statue of Sekhment-Bastet, linked lioness-cat goddesses. As described by the Shorter, “The strangest feature of the object is the cat's face, which is made of bronze attached to the stone figure (the latter shows the ruff, and is therefore properly of Sekhmet) . . . the throne of Sekhmet-Bastet may be easily explained by the fact that [these cat goddesses] are known to be connected.” Linked names created composite gods like Re-Horakhty and combined different aspects similar deities like Atum-Khepri to combine the morning and evening sun. Syncretism

recognizes presence of one god “in” another god when that first god adopts a role that was a primary function of the other. They did not become identical. Reaching outside the sphere of Egyptian religion, Amun’s weapon could be interpreted as a thunderbolt, the same weapon as the Greek god Zeus. Zeus-Amun became a recognized form of the ram sky god in the Late Period because of similar, overlapping attributes.

Religious Relations and Structure

New Kingdom Egypt used triad structure to simplify divine plurality and unity. “In Egypt the triad was an extremely suitable structure for connecting plurality and unity, because the number three was not only a numeral, but also signified the indefinite plural. This is apparent, for instance, in hieroglyphic writing: to express the plural, an ideogram may be repeated three times or three strokes placed after the signs indicating a noun. Thus the triad was a structure capable of transforming polytheism into tritheism or differentiated monotheism.” The triads containing both sexes usually have the family structure: father, mother, and male child. Family in triad structure cannot exist as syncretized gods because of the female characteristic, thus retaining the pluralistic totality. As personalities they remain independent of each other. The most familiar example is Osiris, Isis, and Horus of Abydos. Other examples originated around the larger cities and became cemented during Amenhotep III’s reorganization attempts. Modalistic triads, composed only of male deities not families, have the gods appear under three aspects without becoming three gods. In essence, the members reflect three aspects of one deity. The three forms of the sun associated with the parts of the day, Khopri, Re, and Aten, may be interpreted in this way. A unique example is the Ptah-Shu-Tefnut group that displays traits of both the modalistic and tritheistic triads and, in fact, it seems to represent an intermediary form of the two.

Osiris is the best documented example of how a god “conquered” lesser gods as he adapted and absorbed new symbolism. Osiris, originally a fertility god, assimilated easily with other deities of fertility and the afterlife. Osiris enacted as the “conquering god” by absorbing lands and features of other gods. Andjti, an old man representative of the afterlife, is the oldest known case of syncretism and occurred in pre-dynastic times. Osiris also engulfed Khenti-Amentiu, “Foremost of the Westerners,” in the early Old Kingdom. Osiris became more widespread with his incorporation into Heliopolis Ennead. The Old Kingdom recognized his powers of fearsome judgment but by the New Kingdom all that remained of this was “the terrible.” With the expansion of funerary rites in the Middle Kingdom, Osiris’s popularity spread, and with his spreading, other kings of the underworld died off.

Post-Pharaonic Religious Influences

As Egyptian religion adapted to internal changes within Egypt, so to did it adjust to external influences from foreign invaders. Though the pharaonic age held the apex of Egypt’s religious might, invading peoples failed to weaken the resolve of the Egyptian people both politically and religiously.After 700 BC, pharaohs ceased to be a reliable source for religious strength because control of Egypt changed hands with Assyria, Persia, Greece, and Rome over the next millennium. Bad times in Egypt were ascribed to ungodliness and wavering faith; thus, Egyptians become more devout despite foreign invaders bringing different religions. However, after centuries of oppression, Egyptians became cynical, and many adopted an “eat, drink, and be merry” mentality, parading mummies through feasts to show the purposelessness of life. They held their religion close while embracing despair from the fall of Egypt.

Persian Enmity

Part of the Egyptian’s resoluteness stemmed from their superiority complex. They saw the Persians as superior only in wine making. No people can become obedient and subservient to another when it believes that it is intrinsically better. Herodotus reports that the Egyptians viewed the Persians as inferior in every way except in the art of making wine, a process foreign to the Egyptians. The Late Period does reveal a cyclic nature to Egyptian religion even if that cycle is two-thousand years long. Pre-dynastic deities were almost all animalistic with the falcon and cow representing the cosmos. Pharaonic period gods incorporated human characteristics and mixed various animal forms. The Late Period returned to its origins with gods mainly depicted in animal form.The first major empire to subjugate the Egyptians, Persia, struggled with rebellion its entire reign. Even with attempts to portray the Shah-n-Shah as a son of Re and thus rightful pharaoh failed. Rebellions continued the entirety of Persian rule. Egypt stoutly defended its northern border from Persia, but Cambyses, the son of Cyrus, successfully invaded Egypt. The resulting havoc from his desecration of the Apis bull instigated an Egyptian rebellion that achieved its intent, pushing Persian control back. Throughout this period animal cults reached their peak. Little religious influence transferred to either society from the other. However, Horus of the Horizon, depicted as a winged-disc, increased acceptance of Ahura Mazda in the Syrian region. Egyptian stele standing for centuries with Horus carvings allowed the symbolism of the new Persian religion to re-purpose Egypt’s past glory. Both cultures placed the winged-disc over doorways as a protective symbol.

Hellenic Influence

While Persia failed to absorb any theological lessons from Egypt, the Greeks differed. All non-Greeks were classified as barbarians, but Egyptians nearly reached an equatable standard due to an alliance with Greece against Persia. The Egyptian’s history of seemingly infinite grandeur held Greek merchants in awe. That said of all the lands the Greeks attempted to Hellenize, Egypt resisted the most successfully with almost no permanent impacts. Egyptians resisted conversion to Greek and Roman gods just as their ancestors had resisted a native pharaoh’s law to abandon all gods but Aten. No religious zeal left the Egyptian people in the intermediary years, and true to their ancestors, Egyptians regularly resisted the influence of foreign gods.

In all, Hellenism of Egypt failed because the Greeks became Egyptianized. While Egyptian was supposed to be subservient to Greek linguistically, Egyptians successfully climbed the social structure through the Hellenizing process and became prominent officials that minimized Greek influence on Egypt at large.

The Ptolemaic era’s center of intellectual influence fully embraced Egyptian religion by the end of the second generation. Greek versions of Egyptian myths failed to penetrate the population at large, and Greek settlements along the Mediterranean coast adopted Egyptians myths within decades. The Hellenic cult of Sarapis, a national deity, spread rapidly at this time. The cult spread faster in the Levant than in its Hellenistic-Egypt origin. The Sarapis cult contained both Egyptian and Greek ideas and was adopted as the state religion not for its popularity but as median ground between the two cultural and religious forces. A committee of Ptolemaic scholars sat down and compounded a god out of elements derived from various nations and religions selected to suit the needs of the moment as they understood them: Sarapis sought to attract Greek and Egyptian alike and to form a religious bond.

Egyptian mythology came to influence the Hellenistic world at large. Greeks’ readily adopted Osiris and the Apis bull of Amun in their own cults. Greek settlers in Egypt, a conquered land, were almost unrecognizable to their European counterparts. The emotional individualism that had become characteristic of Egyptian religion post-New Kingdom successfully attracted crowds of new followers as mystery cults came to dominate the religious realm of the Hellenistic and early Roman eras.

Roman Severity

Hellenization failed, especially when compared to the success of the Seleucid Empire since the Greek rulers were Egyptianized. Rome took a much stiffer rule with Egypt by politically regulating Egyptian overseers below Roman citizen status. The most important change to the political system was the stripping of Egyptian priests of land, wealth, and tax exemption. Since this upset the balance of Ma’at, Egypt rebelled against Rome for three consecutive years after the change in religious regulations in 66 AD. Ever resentful towards its master, Egypt rebelled again around 150 A.D. when an Egyptian priest initiated a century long rebellion in which the troops were composed of native Egyptian farmers that had been taxed off their land by Rome.Rome made no impact in altering Egyptian life except in resistance to Roman rule; Egyptians, influential even in defeat, originated a cult that came to dominate the Roman world before Christianity defeated a three thousand year old goddess. Isis, meaning “throne” in Egyptian, served as the devout wife of Osiris with a history dating back before the fifth dynasty. For most of history Isis was not worshiped separately but incorporated into other’s temples, notably connected to Osiris. Not until Ptolemy III were any temples dedicated to Isis specifically which occurred with her increasing fame as the goddess of the most popular mystery cult.

Under the mystery cult which reached its height in the early Roman empire, Isis retained her affinity for healing which references the mythology of her recovering Osiris’s body after his murder by Set. In The Golden Ass when Lucius calls out while standing by the sea for the mercy of Isis to turn him from an ass back into a man, Isis responds by saying that she “represent[s] in one shape all gods and goddesses” and grants his request. This explanation harkens back to Amun-Re’s role of connecting with all other gods. The most popular instrument of choice for Egyptian religious ceremonies, the sistrum, is still used by Isis’s cult followers outside of Egyptian during the Roman period.

The religious procession of the Isis mystery cult, while adoptive of non-Egyptian customs, remained largely reminiscent to the goddess’s Egyptian origin. The Egyptian gods Anubis and Hathor, the bovine goddess of beauty, accompanied the processions. Isis’s golden vase references Egyptian processions of a god’s ka, soul-possessing statue which traveled on a barque through the Nile. Osiris, husband to Isis, remains coupled with her though with less influence than during pharaonic rule. Lastly, ancient Egyptian priests strictly enforced religious scruples; Herodotus respected the sincerity of the Egyptians’ extreme devoutness including sexual abstinence in or the day before entering a holy place, dietary restrictions, and mandatory shaving of the head and body. Similarly, Apuleius restricts his diet for ten days before the initiation ceremony of the mystery cult. When entering the priesthood, Apuleius shaves himself since bodily hair lowered man to the status of an animal and only those that were clean shaven could serve the gods.

Egypt successfully initiated some cultures into its religious ideology with widespread acceptance. Classically, Greece is credited with conquering her conqueror, but to a lesser extent, Egypt seems to succeed as well.

Christian Ascendancy

By defeating it, Christianity made the first lasting impact on Egyptian religion in three thousand years. However, Christianity is imprinted by the Egyptians since Egyptian influence affected all cultures in the Roman period. The modern Coptic church still borrows symbolism from its Egyptian counterpart including abstinence in religious areas, worship of a man as the son of god, and the myth of a dying and rising god though it is not the only modern branch of Christianity with descriptions of the Judeo-Christian god. The Hebrew god Yahweh shares many things with Amun including association with the sky, a bellowing voice, his demand for bull and ram offerings, and control of the waters with their divisions in the heavens and the seas. The king as a both a priest and an intermediary between the gods and the people demonstrates connections to Christianity’s explanations of Jesus as king and priest.

Christianity arose in Egypt in defiance to Rome. The first method involved the wide popularity of monasticism. By withdrawing into the wilderness, large numbers of Egyptians could simply ignore Roman governing practice. The second method of resistance dealt with the organization of the early Christian church within Egypt. Its foundation in Greek theological philosophy ostracized it from Rome, and the Egyptian church hierarchy never aligned with Rome or Constantinople. The most lasting imprint of Hellenization, Coptic, merged Greek and Egyptian letters. Under Roman rule, the lower classes widely used the Coptic language which was eventually adopted as the official language of the Egyptian Christian church.

Egyptian religion died after Theodosius declared Christianity the official faith of the Roman Empire and banned all others. The Egyptian religion continued to be practiced underground until the early fifth century, but its practices were not conducive to secrecy. The political dominance of Christianity in the Roman period expunged these ancient Egyptian practices once foundational for the functioning of Egypt. This also marked the closing of Egypt’s rebellions. No longer motivated by the preservation of Ma’at, Egyptians accepted the Christian God’s eternal salvation from the unknown chaos and darkness so long essential to Egyptian understanding.

The rise of the pharaohs and Egyptian religion alike dominated the government, culture, society, and landscape, of a people for over three millennium. Key to the resilience of this religion was its flexibility and devoutness which allowed the religion to prosper under times of prosperity, famine, and oppression. The Egyptian people’s devoutness to their gods despite the collapse of their empire gives an understanding to how vital the religion was to its worshipers. Resilient despite constant conflict for its last three hundred years, the downfall of Egyptian religion represents the end of Egypt more definitely than the fall of native pharaohs eight-hundred years prior.

Though the great king of the gods, Amun-Re, eventually subsided into the backwaters of the Nile, Isis, an Egyptian creation, continued to testify to the greatness of Egyptian religious ideology and spread throughout the non-Egyptian world. Despite competition from religions of other cultures, Egyptian beliefs subverted most competing practices and became established within their oppressors’ empires. Religiously, Egyptian influence remains within the modern church because of its influences on ancient Judaism and Christianity. Through three millennia, the perseverance and stubbornness of the Egyptian people testified to their passionate following of whomever could justify himself as the son of the gods from pharaoh to Christ.

__

Agatha Tyche

6.11.16

King of the Gods

Amun-Re

The size of a god’s temple reflected his importance since size dictated land claims, herd sizes, and income. The greater numbers of temples dedicated to a god, the more widespread his acclaim.1 It is not surprising then that by the end of the New Kingdom, Amun-Re dominated the religion of the Egyptian people.The religion attributed three common ranks to deities. All people recognized the universal rank. Claimed by Ma’at, Nun, Osiris, and few others, these gods were worshipped by all Egyptians with no known exceptions.2 The major gods, favored by the state, included Re, Amun, Ptah, and well known triads. The most famous of these state groupings, as arranged by the eighteenth dynasty, is the Great Ennead. These twelve gods oversaw the divine birth as established in the Old Kingdom and which remained popular throughout the millennium of pharaonic rule. Each nome had appointed gods that characterized that region. A nome in Upper Egypt dedicated itself to Hathor while one in Lower Egypt declared Neith its patron. Every city also had special gods which were honored with their names and symbols paraded on a stand at festivals. There is no known limit for the total number of Egyptian gods. The lowest order of gods represented familial and personal gods which the lower classes clung to with great affinity. Tauret and Bes are the most commonly exemplified gods of this division and functioned largely as protectors. All gods had special locality of significance, even cosmic gods, and these areas fostered strong association with worship to that deity.

Amun

Amun’s origin remains ambiguous though records of his temples date from the fifth dynasty onwards. During the First Intermediate Period, Amun displaced Montu’s dominance in Thebes and retained that position until the fall of the Egyptian religion. With his established prominence at Thebes, Amun’s relationship with other gods changes. His consort becomes Mut, and he obtains a more war-like character, probably from the militaristic focus characteristic of Thebes. As the thirteenth dynasty in Thebes expelled the remnants of Hyksos rule, Amun’s creditation as a warrior flourished with the upswing of Theban power and is referred to as “lord of victory” and “lover of strength.” Nonetheless, he remains a very diversified character named “the hidden one” which hints at his origin as a sky god. One of the main focuses of his worship dealt with Amun’s concealed knowledge. However, once Amun’s increasing popularity associated him with the creator gods, he was fused into the Ogdoad of Hermopolis, where he became depicted as self-renewing snake.Although Amun’s origin is unknown, Amun and Min have very close associations in the Old Kingdom. However, as Amun’s prominence and association with Re strengthens, Min’s connections are removed. The majority of Egyptian gods ascribed to fertility at some point through their long existence. Amun remains a sky and wind god. As a sky god solar connections became apparent with the Book of the Dead repeatedly naming Amun the “eldest of the gods of the eastern sky,” referencing a primeval and solar fusion of Amun and Re.

The ascension of Amun to king of the gods was long in coming. The pyramid texts of the fifth dynasty depict Amun sitting on a throne, and Middle Kingdom artwork has Amun in the position of pharaoh, ruling over the Two Lands, references to Upper and Lower Egypt. Constant allusions to his deistic dominance do not arise until the fall of the Hyksos invaders.3 In time the Greeks associated Amun with Zeus, both kings of the gods in their own rights.

Through this ascension, Amun became a universal god of the Egyptians. His soul permeated all things as the one in whom all other gods were subsumed. Depicted as human with a bull tail and a double-plumed crown, he represented the wisdom of man with the strength and fertility of a bull as he ruled over Egypt and its gods. His other sacred animals, the ram and the goose, represented his fertility. The goose in particular because its association with water harkened back to his origin as a sky god and control over the heavenly waters. Ram-headed sphinxes decorated many of his temples as is still evident by the avenue of sphinxes at Karnak. By massing them at the entrance to his temples, worshippers had to walk through the many eyes and ears of their god to enter his sacred space, and if the worshipper failed to please him, the stone servants would destroy the doubter.

The annual Opet celebration celebrated Amun as his barque journeyed up and down the Nile, visiting his related gods. This parade through all of Egypt kept his popularity high while reinforcing the power of his priestly servants and, more indirectly, pharaoh who served him on the physical throne of Egypt. With such a strong residency within the population and vast self-sufficient wealth in his temples, Amun could not be destroyed even with the thirty year attack on his sovereignty by Akhenaten. Two dynasties after the Amarna period, Amun’s high priest in Thebes essentially functioned as a second pharaoh in Upper Egypt. Pharaohs sent princesses to marry the high priest; the priestess became known as “God’s wife of Amun” and rivaled the position of the high priest itself in later times. The priestess became widely popular among commoners because of her generosity and sympathy for the lower classes just as Amun advocated for the common man, obtaining titles such as “vizier of the humble” and “he who comes at the voice of the poor.”

Amun, armed with his lightning and meteorite weaponry, controlled the major trend of religious themes for the last eighteen hundred years. One of the eight gods of wind and creation, Amun, Theban King of the Gods, Lord of Creation, and Protector of the poor and weak restored his might after Akhenaten’s attempted assassination of the god. The Hidden One, ruler of the sky, held sway over more Egyptian land than any other god, but this only represents half his power, half his influence, half his wealth, and half his name.

Re

Re, well known Egyptian god of the sun, is easily one of the most important and long-reigning gods of the Egyptian past. He assimilated or coalesced with nearly every god as attested by the innumerable mentions of his name in nearly every temple. Representing the sun at noon, Egyptians credited Re with the flow of every day life as his presence was necessary for light, agriculture, and reproduction. As one of the universal gods from the late Old Kingdom, Re’s position as the sun allowed him to interact with all aspects of creation: heavens, earth, and underworld. The king’s cult dates back to the second dynasty where the king takes the name meaning “son of Re.” From the earliest times, Re, divine father of Horus, protected the king. Re, as father of the king, impregnated the queen in the story of divine birth which later tailored the story to Amun-Re. Though just one of many sun gods, Re was the falcon-headed sun god of all creation. “Khepera symbolized the rising sun and Re personified the sun at noon, when it is most powerful; Aten was the personification of the setting sun.” In the heavens the sun represented both his eye and his body as he daily traversed the body of Nut, the sky god, since the Old Kingdom. On earth Re was the first king of creation and all kings descended from him. In the underworld Re travelled during the night before arising on the horizon each day. This cycle associated Re with every part of life and readily adapted him to worship with other gods. Particular association with Osiris because of travel through the underworld each night resulted in an eventual fusion of the two where the two gods became one in the night, smoothing the mythology of both of their fatherhoods of Horus.

Because of his widespread associations, depictions of him vary by time, location, and other gods associated with particular manifestations. Pharaohs constantly built temples in his honor after the fifth dynasty. This variety demonstrates his versatility, influence, pervasiveness, and power. His symbolism includes a disc, cobra, wings, scarab, ram, falcon, bull, cat, and lion which are associated with him largely through his connections with other gods.

Worship to the sun god expanded through the eras though Iunu, “City of the Sun,” remained Re’s center of worship; the Greeks called this city Heliopolis because of Re’s strongholds there. Pharaoh’s duties involved worship of Re at sunrise when he entered the world from his nightly travels in the netherworld. Along with this, falcon and the Mnevis bull mummifications were performed in his honor. Use of Hymns after the Middle Kingdom became an integral part of worship with a literary height in the New Kingdom. As a creator god, a myth held that humanity arose from his tears of joy at creation. The most steadfast reason for his continued worship was thankfulness since the sun brought light and life each day.

Amun-Re’s Cooronation

These two major gods, Amun and Re, did not gain authority without reason. A local god until the twelfth dynasty with the rise of Middle Kingdom Theban pharaohs, the eighteenth dynasty raised Amun to his position as king. Amun had long been associated with Re through the heavens. The rise of Amun seems sudden compared to that of Re who, from the second dynasty onward, gradually nurses his influence, penetrating hundreds of other cults. A nearly universal god by the fifth dynasty, it took the development of a strong connection with Amun to define the strength of Re’s influence. To make the power and prestige hit home, under Ramesses III, the temples for Amun-Re controlled ten percent of Egyptian land with eighty-six thousand temple workers and priests, four-hundred thousand life stock, and eighty-three ships. Keeping the power that pharaohs had over the religion, especially early on, the originating town of pharaohs at key times in history dictated the course of which gods would expand through political favoritism. As readily apparent, without the rise of Thebes, Amun would not have risen.

As the local deity of Thebes for the Middle and New Kingdoms, Amun rode the wave of pharaonic preference to secure his power before becoming independent of it much as his priests did at the end of the New Kingdom. Amenophis III used Amun as his preferred god to enforce his treaty letters with Caananite rulers, recognizing Amun as the “great god.” This preference allowed Amun’s influence to extend beyond the borders of Eygpt for a time, a rarity for Egyptian gods. Similarly, Re’s prominence grew through associations with pharaoh from early times.

Re’s position was widely recognized as a powerful god. Temple gate writings often invoked the protection of Re in their dedications: “To be said: Oh, Doorkeepers, Oh, Doorkeepers, Oh, Guardians of their netherworld, who swallow souls and eat shadows of the glorified. Apes comes upon them, assigning them to the place of destruction. Oh, just ones, this beneficent soul of the excellent sovereign, Osiris, Ramesses [II], the beloved of Amun, like Re.”4 This stanza shows the power of the king, Ramesses II, by association with the power of Amun and Re. Each gate holds curses for those that disrespect the king, blessings for offerings, and praise to the various other gods, notably Amun and Re.

That the gods could die was reiterated in myths, the necessity of caring for the temples, treasuring the gods’ Rens. Mythologically, Osiris died at Set’s hands. Later periods feared that Re was “decrepitly old” because he had not rested, constantly travelling. This fear lent some justification for the fusion with Amun because it allowed Re to gain extra strength from a dominating name, the king of the gods. Thus, Thebes became a focus area for Re worship and increased the importance of Amun-Re.

Amun-Re’s Culmination

The Amun and Re absorbed and associated with many other gods, not just each other. One of the strongest indications for the late rise of Amun-Re in the canon of Egyptian religion involved the eighteenth dynasty’s organization of gods into triads, typically a father god, mother goddess, and a male child. One of the most powerful families, the Ogdoad of Hermopolis, represented nearly all the most powerful gods. Amun’s nature as god of the air and wind would have suited him for a place alongside the Ogdoad. Moreover, it was not unnatural that the priests there should have wished to connect their city with the great god of imperial Thebes who was then at the height of his glory. By the Nineteenth Dynasty Amun-Re had become so well established there that, as just has been shown, Ramesses II thought it necessary to found a temple for him. Further integration into the mythological past involved Amun as a creator god. Each subsequent generational pairs of gods consisted of a male and female. Amun created Shu and Tefnut who birthed Geb and Nut who completed the lineage of the king since Re-Osiris was one of their sons. Nonetheless, flexibility is permitted because although there is a multiplicity of approaches to Egyptian religion, all are correct.

Horus never successfully absorbed Amun like so many other sky gods. However, Amun absorbed a large contingent of sky gods which were depicted as rams. This connection allowed Amun to gain widespread popularity and strong association with the ram as his sacred animal. Absorbing other gods’ attributes strengthened a god through widening his worship and power base. “Finally, the more terrible aspect of such a god became emphasized in a compound form, which approximated Amun more closely still to his less placid relatives of the more northern skies.” Amun championed integrating other gods into himself. Re, alternately, grew stronger by association while leaving the other gods largely intact.

Gods closely associated with Amun and Re also experienced positive reinforcement. Mut, wife of Amun, became the queen of the gods in Thebes, a new position which did not develop until the Middle Kingdom. Mut had previously been a very minor deity, a familial goddess of the house that rose to pharaoh. Nonetheless, she remained an independent god associated with Amun and was never absorbed even at the height of the eighteenth dynasty’s reorganization. Pharaoh’s imagery as the living embodiment of Hours encouraged the fostering of Re’s universal worship. Re-Horakhty, “Re who is Horus of the Horizons,” gave a positive feedback loop between pharaoh and any cults associated with Re.

Two key terms to understanding the success of both Amun and Re deal with the ability to connect to characteristics of other gods. This flexibility accounts for a great deal of Egypt’s religious resilience in later periods. Amun’s most common technique, henotheism, involves absorbing another god entirely. Henotheism, the worship of one supreme God while recognizing lower deities, allowed Amun to continually heighten his power. The end result is one god with expanded powers, symbolism, and regional influence. Syncretism is the alternative, adapting attributes and associating with other gods’ strengths and the key to Re’s widespread influence.5 Egyptians seem to have preferred syncretism.

By the nineteenth dynasty, stele indicate that Amun and Amun-Re were inseparable, probably due to Amun’s henotheism. Re managed to remain separated because of syncretism. While temples dedicated to Amun and Re existed at Hermopolis, no temple for Amun-Re existed until the nineteenth dynasty when a large section of Amun’s temple underwent construction to alter it. The process of henotheism is difficult to understand because of the complex variability involved in associating one god with another so closely as to engulf it completely. Sometimes the starting-point is not plurality but unity, which is differentiated into three

[distinct gods]. In the sun-god, the rising sun, Khepri, the midday sun, Re, and the setting sun, Aten, are distinguished, and these modalities are joined in the name Khepri-Re-Aten. The gods Ptah, Sokar, and Osiris could be conjoined and depicted as a single being: Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. The great majority of texts regard this composite god as singular. In a few cases, where the third person plural is used of [Ptah-Sokar-Osiris], he seems to be looked upon as a plural being.

Indeed, it seems that gods could be viewed as distinct or conjoined depending on need and context. A temple wall reads, “The pantheon is a triad who do not have their equal. Hidden is his name as Amun. He is Re in countenance. Ptah is his body.” Amun-Re-Ptah, a powerful triad, represented characteristics of all three gods but took on a single, separate identity that blended the individual entities. The triad, if composed of all males, allowed each beings characteristics to mix. Sky gods often absorb other cults to encourage larger followings. Thus, by the end of the Eleventh Dynasty, Amun associated with Re to control the sun.

All Egyptian gods held many names. Hathor, goddess of beauty, had a new name for each day of the year. Re had over seventy-five independent of his associations with other gods. Amun had an “unknowable number” because his character as the Hidden One caused him to withhold information. Combining the known names for Amun and Re results in a third of all known names of the Egyptian gods. Just as their names, depictions varied. Late Period descriptions of Amun-Re give him four heads, seven-hundred-seventy-seven eyes, and a million ears to enhance his omniscience, omnipresence, and care to his worshipers individually.

1 Temple size and number of a god often explain favoritism of the pharaohs, not popularity among the people. Over the extended period Amun-Re ruled as king of Egyptian gods, the masses accepted his standing and supported the increase in his influence throughout Egypt.

2 While representative of justice and order, the goddess Maat also embodied justice and was responsible for weighing the heart of the judged dead. The line between the goddess and process whereby the pharaoh ruled with justice are nearly indistinguishable without context even on Egyptian sources. Represented by an ostrich feather, Maat’s popularity among the Egyptian populace was long lived and integral to mundane activities.

3 These declarations of Amun’s power come from his status as the prominent god of Thebes. When Thebes expelled the Hyksos and founded the Middle Kingdom, Egypt looked both to Theban pharaonic and religious leadership.

4 Mohamed Abdelrahiem, “Chapter 144 of the Book of the Dead from the Temple of Ramesses II at Abydos,” Studien zur Altagyptischen Kultur 34, (2006), 5-6.

5 While Henotheism means the worship of a supreme god with recognition of others, the Egyptian case follows this example to the extreme with the supreme deity becoming powerful enough to disestablish the cults of similar gods entirely.

__

Agatha Tyche

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)